Katelynn rogers

Katelynn and I are new and fast friends. We met through another dear friend at an opening at RISD, only a month before we graduated and parted ways. I have learned the hard way that fast friendships can end in disaster on more than one occasion, but with Katelynn there seems to be nothing hiding behind who she says she is – if you’re lucky enough to meet her you’ll find a great familiarity in her presence; and whether you see her photos or self first, one cannot be separated from the other. She is her work as much as an artist can be, leaving her entirely unmysterious in the best kind of way. I feel lucky to know her and in this interview I hope you feel you’ve met her, too. I believe you’ll find as much in her as I do if you look the right way. So before I ramble on too long, I am happy to introduce you to Katelynn Rogers of Canton Ohio; both as a darling friend and marvelous artists.

***

Katelynn and I share a somatic connection to the lands with which we discovered our deepest hardships and the total consumption of existing in wait for something better. As I’ve written more openly about my life in Colorado, I’ve found many of us share a disconnect with the land where we were severed from ourselves. Sharing Katelynn’s work with you, my beloved readers, seems only fitting.

Our last week together in school was spent at the McDonald’s drive through between our homes in Providence, and I have no doubt we will be lifelong friends. In her I see a reflection of myself I have yet to find in another woman, a reflection that I find in her artwork which deals with the body in an eerily similar contortion to my own.

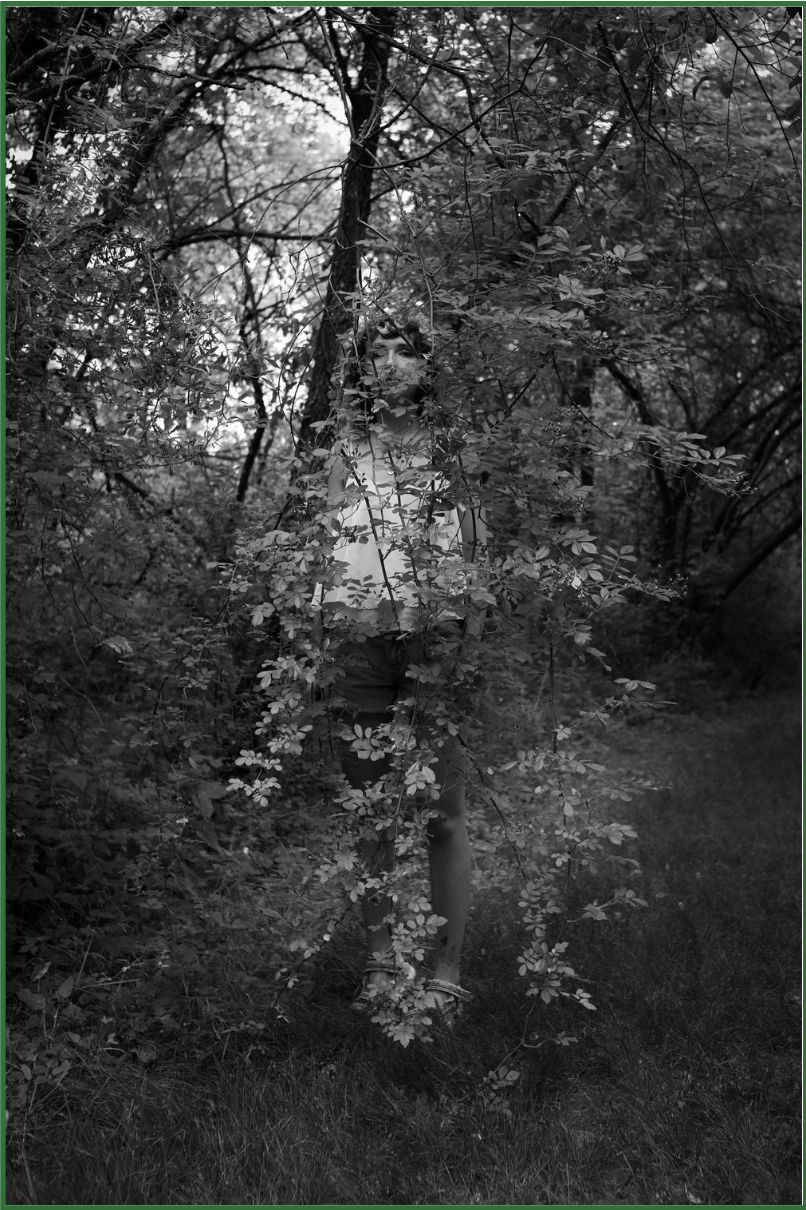

Katelynn is a photographer, a self portraitist, and a writer. Her work encapsulates her curiosity of motherhood, desire, and limit. She weaves her own experiences with the women she is most deeply conjoined to, and though her photographic investigations are largely made up of body and wilderness, there is always a visible thread of searching. What that search is varies, but there is an absence of women and their potential well being within the trails her eye follows; as if we are viewing footsteps of someone before her. In her hometown of Canton Ohio, Katelynn brings us closer to things that aren’t there for us to see, but feel. Her images of both forestry and body offer a balance of gracefulness and disturbance.

I find myself behind her eyes when I look through her unedited lens, and I can’t help but think her eyes are that of all of us, whether we want to relate to her pains or not. Her work is about what undeniably is. Her voice and oculus leave us with no questions about how she lives, and I owe that honesty to the quickness of our friendship. We’re both unable to sensor ourselves, which gets us both in trouble more often than not. She’s a storyteller of lives lived and unlived, a narrator of womanhood’s most cruel burdens that can be felt by anybody close to femaleness, cis or otherwise. You, the reader and viewer, will undoubtedly find yourself surrounded by Ohio’s spaciousness and haunt as Katelynn guides your eye towards the unseen. I invite you, urge you, to let yourself take time with her pictures, for there is always something hiding behind the immediate.

When did you find photography and how were your beginning years with a camera? Though your work has evolved after so many years of working, what has remained present throughout those years?

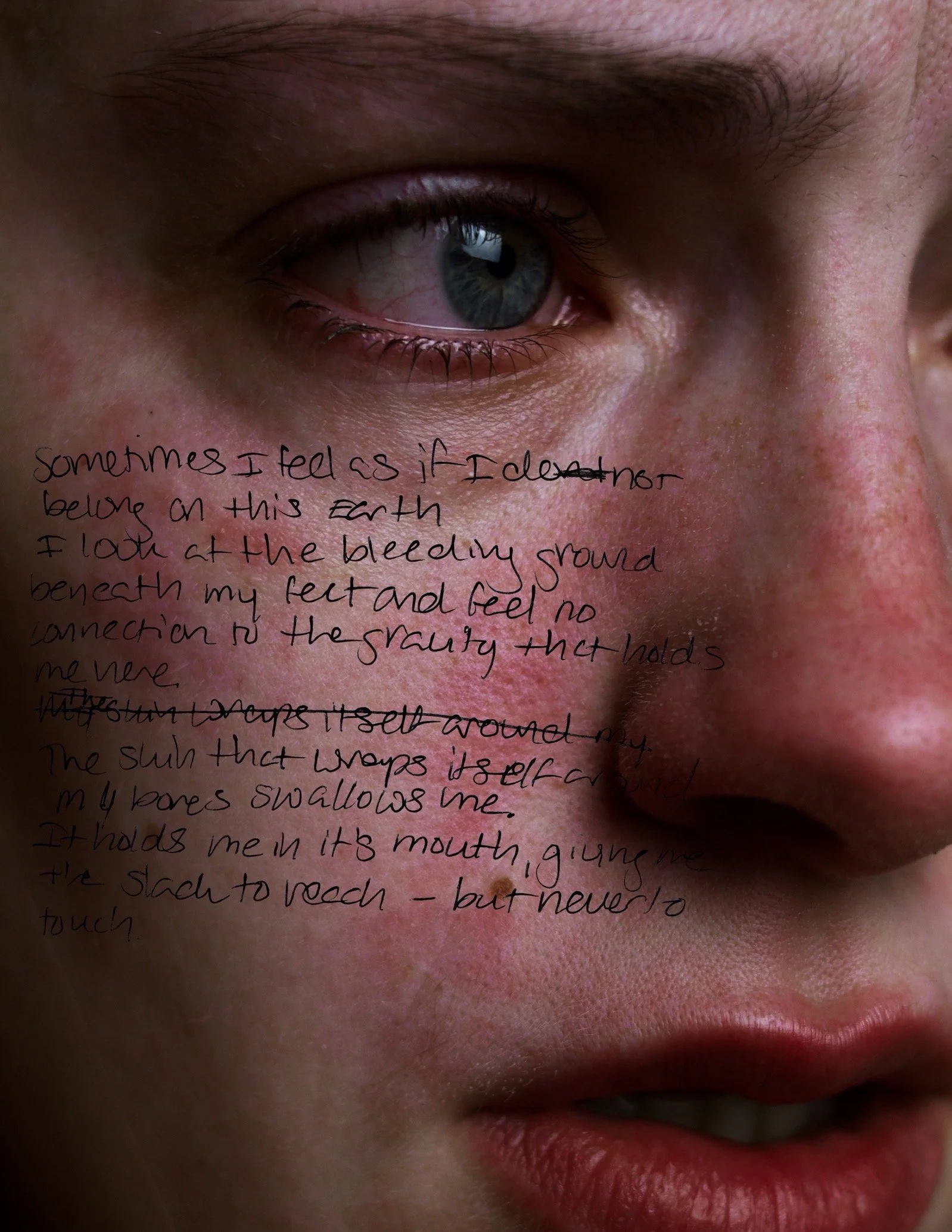

Photography came into my life after a creative lull in my teenage years. Writing was actually my first love. Somewhere in a storage unit, I have a giant stack of journals of handwritten, scribbled poetry that I filled over a matter of months in my early teens. At the time, I was overflowing with energy and passion. Words melted into the margins and stacked on top of one another, making some of the journals impossible to decipher now. Poetry was such a wonderful and addicting form of release. I was even chosen to join a competitive writing team and won a handful of awards for my written work before reaching high school.

When I was fifteen, I began experiencing sexual abuse from my much older boyfriend. Living in conservative Ohio, I couldn’t bring myself to admit that I had been having sex, even if it wasn’t consensual, to the adults in my life. Embarrassed and unable to speak about what was happening, I came to realize that writing about it would be another form of admission. So, I just stopped writing completely. I started to have debilitating panic attacks in school, and would break down in tears in English class because I couldn’t bring myself to write a single word. Where I was once overflowing creatively, was now barren and empty. Part of my ability to express myself had withered away. I was beginning to self-implode from the weight of the trauma, and quickly resorted to self-harm to cope with not only the aching from the abuse, but the loss of my favorite artform.

I was given my first iPhone that same year, and quickly realized the camera had a self-timer. I don’t remember why or what led me to setting the phone up and posing in front of it but once I did, I never looked back. Through self-portraits I could express the intensity of my sadness without having to explicitly tell anyone what had happened. Even now over a decade later, photography is the crutch I’ve continued to lean on for expression and release in the times when words fail me. After miscarrying in 2021, I immediately threw myself into a photography project as a form of processing what the hell had just happened to me. A beautiful side effect of photography’s existence in my life has been the way it has allowed me to understand others, specifically the women, in my life. While the self-portraits have evolved drastically over the years, they are ever present in my work.

Self-portrait, 2016.

Self-portrait and poetry, 2020

What does the word ‘missing’ mean to you?

The word “missing” is loaded to me. It feels like this thread that is constant in every detail of my existence. My father was adopted in a closed adoption in the late 60’s, and I think the absence of knowing that side of my family has always sat strangely with me. For example, I have a very distinctive dimple on my top lip–a feature I don’t share with anyone else in my family. I look at strangers constantly, searching their faces for that dimple. While I loved my Grandma Dee deeply and dearly, I still keep looking for the woman I carry the face of. A woman whose face is absent in my life except within my own reflection.

Untitled Self-Portrait, 2024.

For me, the word “missing” has meaning beyond something that was removed. These days I think of its meaning more of something that never was, something that may never be. When I found out I was pregnant, I ended up miscarrying only a week later. After the bleeding stopped, I couldn’t help but wonder why it even happened in the first place, what was the reason for something to exist so briefly…But not even end up existing at all? I still have strikingly vivid dreams about the miscarriage, and the emptiness that settles in my body following those nights is something I can never shake.

Perhaps this lack of resolution, a constant state of wondering “why” is what haunts me the most when I think of the word “missing”. When I see Caitlyn Kingery, one of my dearest friends and long-time collaborators, I see a woman whose mother seemingly vanished into thin air. Tammy’s absence is ever present, and melts into every detail of Cat’s life. In the decade since Tammy’s disappearance, Caitlyn has never been offered a moment of reprieve or clarity into understanding why or where her mother slipped away. I think that’s why Caitlyn and I connect so effortlessly, we’re both trying to understand what loss means through photography. Our images don’t provide explicit answers to the questions of “why”, but rather explore the haunted energy that the emptiness left in the first place.

You are a Midwestern girl inside and out. How does your relationship to rural America connect and disconnect you from the Northeast where you’ve resided for the last two years. How does it feel to return home?

When driving from Rhode Island back to Ohio this June, I could tell the moment I crossed into the Ohio state line based on the change in the trees. There is a familiarity and comfort that washes over me in each return, I know this place and it feels like it knows me too. Over the past seven years I’ve been in and out of Ohio constantly, living in Chicago for undergrad and then moving to Providence for grad school – but returning each summer and winter for weeks, sometimes months, at a time. When I made the choice to move to Chicago back in 2018, it was in pursuit of an education that would truly challenge me–opportunities I felt like Ohio lacked. I kept waiting for Illinois to feel like home, but instead my time in Chicago left me feeling like a shell of myself. The November before my graduation is when I lost the pregnancy. I felt like I was in a state of limbo for the rest of my time in the city. By the time I left in 2023, I still hadn’t let myself put screws in the wall of my apartment because I knew I wouldn’t, couldn’t stay there.

I could have easily permanently returned to Ohio and my family to cope with the aftershock of the miscarriage, but Ohio’s right wing politics left me petrified about the future of my existence within the state. It no longer felt like the safe haven I had imagined it to be. My move to Providence felt like a desperate escape from Chicago and the trauma I had endured there. Rhode Island, graduate school, it was my chance to begin anew. Of course, moving was only smothering the wound with a bandaid. It was within my brief returns to the woods of Ohio that I was able to slowly dissect what had happened to me through making images in the woods of my hometown. Finishing Covered in Snow felt like the first time I truly let the wounds from the miscarriage breathe, exist freely. My school, my new friends, the love I encountered along the way, softened me. I even found a patch of woods in Massachusetts that somehow felt exactly like the terrain of Ohio and snuck a few into the book.

The choice to return to Ohio following graduation from RISD has felt like a giant risk. I read an article today that mentioned that discussion of criminalizing abortion is happening in the state yet again, despite abortion supposedly being protected in the Ohio state constitution. The lack of opportunities and room for artistic growth that caused me to leave the state initially in 2018 are still an issue. I want so badly for Ohio to be this place of regrowth, but the feeling of placelessness, the fear of putting holes in the wall, is still present.

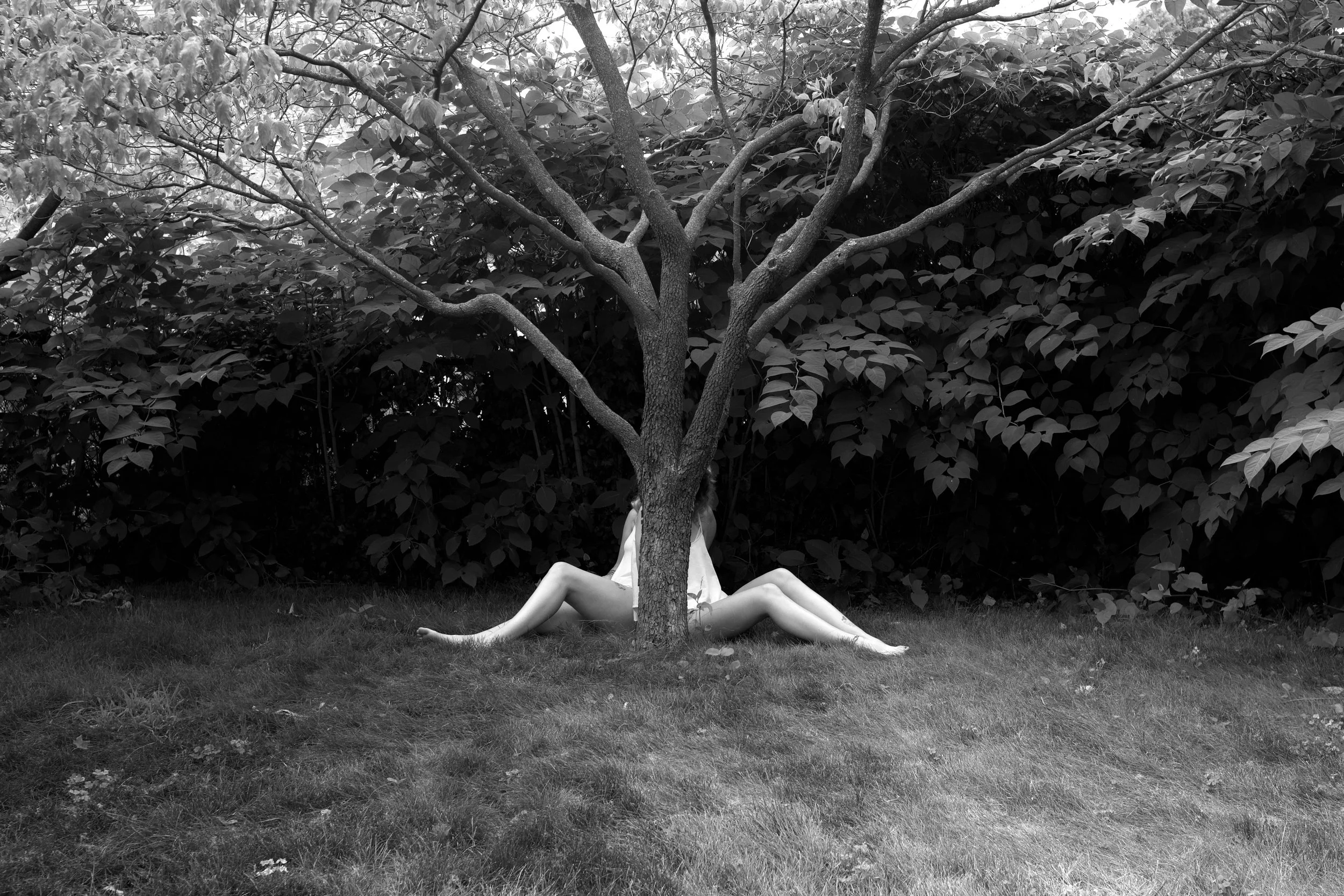

You are often alone in the woods, something many women are fearful of. You’ve described finding yourself attracted to risk, what do you think you’re looking for when you photograph a landscape where you’re truly alone, or at least hoping to be?

When I began writing my thesis, I realized there was a level of suicidal ideation intertwined with my obsession with hiking in spaces connected to the deaths of women. I knew that the trees I hiked past were both witnesses and perpetrators of violence, yet this knowledge drew me in deeper. I was struggling to understand my trauma, not just the miscarriage, but the trauma I had been using photography to cope with my entire adult life. There were times when I would walk into the woods and wish that the trees would swallow me whole. I never explicitly thought of how I would kill myself, but the feeling of wanting to vanish would be overwhelming at times. Additionally, I struggled with the reality that I walked the same paths as each of the women in Covered in Snow, yet I got to leave the parks at the end of the day and they didn’t. These were women who were daughters, sisters, mothers, all of whom wanted to live, and here I was, someone unsure about my desire to exist, and I was still alive.

Violent Nature, 2024

I wanted desperately to show the weight of my internal turmoil in these spaces. Part of me had a macob fascination of what my body would look like if it was found dead, which is why I began taking self-portraits of myself tangled in brush. I even made plaster casts of my hands and scattered the pieces in the grass for an image, just to have an idea of what my body would look like as it broke apart. When I had first learned about some of the assaults in Ohio state parks, I wondered how hidden their attackers had been. When Caitlyn Kingery came to visit me last year in my hometown, we played a form of hide and go seek in the woods, just to see how easy it would be to go undetected amongst the trees. We filmed each other as we “hunted” for one another. That footage never made it into any body of work, something about rewatching it scares me even though its two girls giggling as the run around the woods–part of me is convinced one day I’ll watch the footage and see another set of eyes watching us.

Stills from Caitlyn and I chasing one another, 2024

Does the possibility of being followed or tracked ever influence your trips outside? How does your body and intuition physically react to your surroundings? As a woman, undoubtedly postulated as an animal of prey in American society, do you feel transformed into something beyond ‘girl’ when you hunt for images?

While investigating the women who had died from accidents in the Ohio woods, I came across a handful of articles that detailed different assaults and murders that have occurred in the same spaces. There is a park I photograph at regularly where an unnamed woman was attacked in an attempted kidnapping, and her story sits with me every time I return to those woods. She had successfully stabbed her attacker, but he still vanished into the woods and was never found. It’s impossible to read encounters like that and not have it influence your choices of when / where you’re willing to hike alone. There have been times I’ve driven an hour to a specific park to photograph, but when I arrive I feel something deep in my bones telling me I shouldn’t be there. I’ve learned to trust my intuition, but even then I know my gut isn’t going to be what saves me from a man.

(Portrait of Caitlyn Kingery at Quail Hollow, where the unnamed woman was assaulted)

Now when I hike, I try to embody the behavior of a deer. Moving silently, swiftly, always looking and listening. I even follow deer trails fairly often, many of the images I’ve made in Covered in Snow came from following these paths. While it may be silly, I also try to dress like a man when hiking alone. I braid my hair and tuck it into hats, I wear bulkier clothing. My tripod bag also resembles that of a bag for a hunting rifle. This process is a bit easier in the winter, when I can hide under my giant Carhartt jacket and snow pants. If I know the goal is to take a self-portrait, I hike that same trail multiple times to assess when it feels the safest. The woods have granted me reprieve and regeneration, especially while healing from the miscarriage–but I miss the days of carelessly hiking with my friends and creating on whims. I always wonder about the images that could have been, if I hadn’t felt scared to pause and shoot.

Doe Diptych, 2025

Describe your fascination and relationship to motherhood. How have your experiences with young mothers, missing mothers, and the emotional turmoil of your miscarriage shaped and changed your relationship to the female experience? Do you find yourself primarily resonating with the women you photograph or searching for resonance?

I think I was destined to be obsessed with motherhood in a unique way from day one. Growing up, my mom was very open about her own mother’s death. My mom was only 23 when my grandmother, who was in her early fifties, died from a rare degenerative condition. While I have brothers, I’ve always felt that my relationship with my mom has been different. I can sense her longing for her own mother daughter relationship in the tender, yet sometimes oppressive, way she’s raised me. My mother became very ill right before my birth, and has dealt with a horrific case of Crohn’s disease in the 26 years since. Seeing her strength through her own grief and ailments, all while raising me and my brothers, was immensely inspiring. She’s had every setback imaginable, but she still achieved every one of her dreams. She is genuinely the most badass woman I’ve ever met. When I got my first 35mm film camera at 16, I would force her to pose in lighting tests. She was very brave and let me photograph her constantly, even when I was taking god awful pictures.

My Mother and I, From Letters From Our Mothers

I was shy and very depressed as a teenager, which made it hard to let people into my life. I made a small number of friends that I trusted enough to share my art with, and they all very bravely allowed me to photograph them while showing unbelievable levels of vulnerability. One of those women, Courtney Allen, was the first woman I had ever known who had a miscarriage. Throughout her journey from being a teenage girl, to a grown woman and mother of four, she has let me photograph her constantly. The level of trust she has shown me is something I’ll never take for granted.

Courtney and Aria, From Letters From Our Mothers

When I finally met Caitlyn Kingery in undergraduate school, we connected immediately and photographed one another obsessively. I didn’t know about her mother’s disappearance until about six months into our friendship. Upon learning about her mother, the images we had been making our entire friendship transformed before me. When I miscarried a year later, I looked at these women who surrounded me and realized they had all been touched by grief in a multitude of ways. I made a book, Letters From Our Mothers, my senior year of college as a love letter to them, but the images were all archival work I had made of them over the course of almost a decade. It was like I had always been working on that project, long before I even had the miscarriage. I was, and still am, enamored by these women, and the trauma I encountered brought me even closer to them.

Self-Portrait with Caitlyn, From Letters From Our Mothers.

You are a shameless romantic. How does your desire for special connections influence the deepness of your platonic relationships? When you include your friends in your projects, there is a palpable consideration of their essence. It doesn’t feel like you are using them as vessels to deliver your own perspective. They feel collaborative, which is undeniably romantic. At the same time, your work is not fantastical or delusional. How does romance and reality play a role in your life?

The women in my life are electric and fascinating, and they all have one thing in common: they are not just friends, they are soulmates. I don’t know how to be just casually friends with someone, it’s kind of an all or nothing type of deal. Even when you and I met, it was an instant connection that was so vibrant and strong. It was like you had always been there!

Making images of my friends feels like the strongest way for me to express my love and admiration to them. There was a time when getting together to take photos was the only way I knew how to be social, but Courtney and Caitlyn never once questioned it. They let me bring my camera and do my thing, even searching for new places to take me so I could make work. When I was depressed and stuck in Chicago, Caitlyn would take the train to Indiana with me so I could photograph there instead. Even in the times my friends and I were dressing in costume or directly referencing Pinterest boards, I think a grounding element of the work we make together is our love and appreciation for one another–it makes everything else melt away.

Katelynn / Caitlyn, 2024

My biggest fear in including my loved ones in projects is seeming as if I’m “using” them. I don’t want to tell their story for them, or make their pain about me. Finding ways to integrate their voice into my images has been really important to me. For example, around three years ago Caitlyn and I both had dreams about one another. When creating the body of work I Can’t Live Here Anymore, I had Caitlyn to transcribe her dream in her hand writing. I then hand sewed her transcription into the completed book. Having her handwriting against my images was such an emotional, and important moment for the work. Caitlyn is also a photographer, so we balance our time together to work on both of our bodies of work.

I’ve also been learning to let my guard down and remove the camera from social interactions, valuing our connections outside of art–which in turn makes the art even richer. I think female friendship / connection will always be a core element of my work, the women in my life inspire me deeply.

You are the only girl in your family besides your mother. How has growing up with men emboldened your fascination with women? Do you discover more about women in opposition to the habits of hypermasculine men or in their unity?

Part of why I’ve been quick to focus more on the women in my life comes from the fact that I’ve always had complicated relationships with the men in my family. When I was growing up it was very hard for me to connect to my brothers, to my dad, and especially my stepdad. It seemed like they all meshed so naturally, I couldn’t understand what made me different. My eldest brother dealt with a lot of anger issues when he was a teen, which resulted in physical abuse towards me. It was something beyond normal sibling brawling, it was really violent. I wanted to be a girl who could take a punch and not cry, so I became a girl who could take a punch and not cry. If they wanted a reaction from me, I wouldn’t provide it.

It took me a long time to come to terms with how abnormal this dynamic was. I remember meeting a friend who was very close to her father and siblings, which left me utterly confused. I had never been able to talk to my family, even my mom, in such a relaxed way. I want to say that these foundational cracks haven’t impacted me, but I see the repercussions of them everywhere–especially in the men I allowed into my life up until quite recently.

With that being said, things have changed a lot for my family. My oldest brother and I are closer now, and the wounds from our childhood have healed. We’ve come to realize while we encountered different hardships, we have similar scars from our childhoods. We both struggle with communicating about emotion. Where I shut down verbally, he is overly blunt. We are both deeply invested in our friends, extremely loyal to the ones we love. I’d love to do a project about the men in my family sometime, I think the roots of that work are already forming.

Untitled, 2025

(I don't know if this fully answers the question….I tried)

What artists and media have shaped your practice most profoundly? Do you remember what made you want to pick up a camera for the first time?

Oh god, what a good question. For even more context, I have a background in both dance and filmmaking. I did contemporary ballet for about fifteen years of my life. While I hated dancing in front of others, I spent hours every day practicing alone and mimicking movements from music videos. I remember being in an absolute trance over Florence + the Machine’s “Drumming Song” when I was like...12? I rewatched the video recently and giggled because my work ended up being SO different, but if you pause during certain poses in the video you can see movements I still mimic in my work today. Seeing how dance and video could intertwine definitely piqued my interest. I’m sure somewhere online there are some cringe videos I made in high school while exploring filmmaking as a medium. When I left for Chicago in 2018, it was to pursue a degree in Cinematography. Luckily, I quickly realized I am not a team player and changed majors. My practice was meant to be more intimate, more still.

A Study in Movement, 2019

My work, and my mood, feel very tied to music as a storytelling method. I know you and I bonded over the work of artist Ethel Cain. The eerieness of her music along with my familiarity to Ethel’s story arc is a devastating and beautiful combination. Long before I had Ethel Cain, I had the band Daughter. I remember stumbling across their work when I was 15, and it’s been strange seeing how their lyrics follow me throughout my adult life. From surviving abusive relationships, to having complicated bonds with our parents, to the use of self harm, I felt like their lyrics embodied everything I had been silently struggling with. I don’t know what in my brain is activated when I listen to artists like Ethel Cain and Daughter, but it’s like a switch is flipped on and I can just see the image that needs to be made. I hope that you can still see my love for dance within my work, because it still feels like such an important element.

Self-portrait, 2025

You are a writer and bookmaker as much as you are a photographer. Can you describe your relationship to the process of bookmaking? Spending so much time with an art object gives us an additional layer of you and how careful you are when curating the pacing and attention with which we should view your work. Can you give readers an idea of how you sewed your thesis book?

I discovered book making almost directly after my miscarriage in 2021. By some act of fate, I had signed up for a documentary book making course for the upcoming semester. When spring classes began and I had to decide what to make my documentary project about, I knew I needed to make something about the miscarriage. The book that followed was Letters From Our Mothers, and it acted like a love letter to the women in my life who had also experienced loss. Like I had touched on earlier, it was made entirely with archival work. Through the practice of sequencing I could piece together a story that had been in the making for years. Leaving my senior year of undergrad with that book finished felt deeply important, I was leaving with something tangible. The book was something I could hold, it had weight to it. Being able to hold a project like that to your chest feels unreal. I went on to take two more classes on book making throughout my undergrad and graduate experience. I wanted to know as much about the practice as I could.

When it came time to make my thesis book, I wanted the material to be treated with as much tenderness as possible. Making it myself just felt like an obvious choice. The book is a dos-a-dos, so it opens on both sides. The structure could perfectly hold the tangle of narratives I was writing about, reflected by the image sequence on the opposing side. The light blue book cloth and soft yellow binding were chosen to mimic the forget me not flower. I chose to hand-sew the signatures of the book using a French twist, a binding that intertwines within itself as it crawls up the spine. Each of the pieces coalesced into a structure that itself was a Z-shaped web, holding the narratives together with tenderness. For some god forsaken reason, I made 11 copies of the 140 paged book, but it was such a rewarding process.

Covered in Snow, 2025

Anything else you want to talk about

Ur the best thanks for ur patience

Article written by Maren Curtis